fashion min122

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Clothing of China. |

Chinese clothing is ancient and modern. Chinese clothing has varied by region and time, and is recorded by the artifacts and arts of Chinese culture

Contents

[hide]Dynastic China[edit]

Main article: Han Chinese clothing

Traditional Chinese clothing is broadly referred to as hanfu with many variations such as traditional Chinese academic dress. Depending on one's status in society, each social class had a different sense of fashion. Most Chinese men wore Chinese black cotton shoes, but wealthy higher class people would wear tough black leather shoes for formal occasions. Very rich and wealthy men would wear very bright, beautiful silk shoes sometimes having leather on the inside. Women would wear silk shoes, with certain wealthy women practicing bound feet wearing coated Lotus shoes as a status symbol until in the early 20th century. Men's shoes were usually less elaborate than women's.

Civil and military officials[edit]

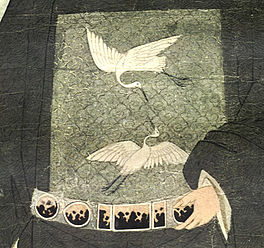

Chinese civil or military officials used a variety of codes to show their rank and position. The most recognized is theMandarin square or rank bad In. Another code was also the use of colorful hat knobs fixed on the top of their hats. The specific hat knob on one's hat determined one's rank. As there were twelve types of hat knobs representing the nine distinctive ranks of the civil or military position. Variations existed for Ming official headwear. In the Qing Dynasty different patterns of robes represented different ranks.

Qing Dynasty (1644–1967)[edit]

The rise of the Manchu Qing Dynasty in many ways represented a cultural rupture with the past, as Manchu clothing styles were required to be worn by all noblemen and officials. The Qing first implemented queue laws that required the populace to adopt Manchu hairstyles and clothing under pain of execution. Eventually, this style became widespread among the commoners.[1]

A new style of dress, called tangzhuang, included the changshan worn by men and the qipao worn by women. Manchu official headwear differed from the Ming version, but the Qing continued to use the Mandarin square. It was around this time that foot binding became more popular.

Republican era[edit]

The abolition of imperial China in 1912 had an immediate effect on dress and customs. The largely Han Chinese population immediately cut off their queue as they were forced to grow in submission to the overthrown Qing Dynasty. Sun Yat-sen popularised a new style of men's wear, featuring jacket and trousers instead of the robes worn previously. Adapted from Japanese student wear, this style of dress became known as the Zhongshan suit (Zhongshan being one of Sun Yat-sen's given names in Chinese).

For women, a transformation of the traditional qipao (cheongsam) resulted in a slender and form fitting dress with a high cut, resulting in the contemporary image of a cheongsam but contrasting sharply with the traditional qipao.

Early People's Republic[edit]

Early in the People's Republic, Mao Zedong would inspire Chinese fashion with his own variant of the Zhongshan suit, which would be known to the west as Mao suit. Meanwhile, Sun Yat-sen's widow, Soong Ching-ling, popularised the cheongsam as the standard female dress. At the same time, old practices such as footbinding, which had been viewed as backwards and unmodern by both the Chinese as well as Westerners, were forbidden.

Around the Destruction of the "Four Olds" period in 1964, almost anything seen as part of Traditional Chinese culture would lead to problems with the Communist Red Guards. Items that attracted dangerous attention if caught in the public included jeans, high heels, Western-style coats, ties, jewelry, cheongsams, and long hair.[3] These items were regarded as symbols of bourgeois lifestyle, which represented wealth. Citizens had to avoid them or suffer serious consequences such as torture or beatings by the guards.[3] A number of these items were thrown into the streets to embarrass the citizens.[4]

Modern Usage[edit]

Hong Kong clothing brand Shanghai Tang's design concept is inspired by Chinese clothing and set out to rejuvenate Chinese fashion of the 1920s and 30s, with a modern twist of the 21st century and its usage of bright colours.[5]

Some Chinese luxury brands like Shanghai Tang.[6]also NE Tiger [7] Guo Pei[8] as well as Laurence Xu.

For the 2012 Hong Kong Sevens tournament, sportswear brand Kukri Sports teamed up with Hong Kong lifestyle retail store G.O.D. to produce merchandising, which included traditional Chinese jackets and Cheongsam-inspired ladies polo shirts.[9][10][11]

Image gallery[edit]

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- ^ Manchus and Han: Ethnic Relations and Political Power in Late Qing and Early Republican China, 1861-1928 by Edward Rhoads, pg. 61

- ^ a b Łukasz Sęk. "Chiński bucik królowej Marysieńki Sobieskiej". www.it.tarnow.pl (in Polish). Retrieved 7 July 2014.

- ^ a b Law, Kam-yee. [2003] (2003). The Chinese Cultural Revolution Reconsidered: beyond purge and Holocaust. ISBN 0-333-73835-7

- ^ Wen, Chihua. Madsen, Richard P. [1995] (1995). The Red Mirror: Children of China's Cultural Revolution. Westview Press.ISBN 0-8133-2488-2

- ^ Broun, Samantha (6 April 2006). "Designing a global brand". CNN World. Retrieved 2 June 2012.

- ^ Chevalier, Michel (2012). Luxury Brand Management. Singapore: John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-1-118-17176-9.

- ^ http://www.ne-tiger.com/

- ^ http://www.guopei.fr/

- ^ "G.O.D. and Kukri Design Collaborate for the Rugby Sevens". Hong Kong Tatler. 16 March 2012. Retrieved 19 November2012.

- ^ "G.O.D. x Kukri". G.O.D. official website. Retrieved 19 November 2012.

- ^ "Kukri and G.O.D. collaborate on HK7s Range!". Kukri Sports. Retrieved 19 November 2012.

Further reading[edit]

- Watt, James C.Y. & Wardwell, Anne E. (1997). When silk was gold: Central Asian and Chinese textiles. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art. ISBN 0870998250. External link in

|title=(help) - Jian, Li & Li, He & Sung, Hou-Mei & Shengnan, Ma (2014). Forbidden City: Imperial Treasures from the Palace Museum, Beijing. Richmond, Virginia: Virginia Museum of Fine Arts. ISBN 978-1-934351-06-2.

.JPG)

22:01

22:01

Qasimrathore.blogspot.com

Qasimrathore.blogspot.com

0 comments :

Post a Comment